Computing heritability

Computing heritability.

We will use the simulated gryphon dataset (download zip file ).

We need to load both the phenotypic data gryphon.csv and the pedigree gryphonped.csv.

phenotypicdata <- read.csv("data/gryphon.csv")

pedigreedata <- read.csv("data/gryphonped.csv")

The phenotypic data look like this:

head(phenotypicdata)

## id mother cohort sex birth_weight tarsus_length

## 1 1029 1145 968 1 10.77 24.77

## 2 1299 811 968 1 9.30 22.46

## 3 643 642 970 2 3.98 12.89

## 4 1183 1186 970 1 5.39 20.47

## 5 1238 1237 970 2 12.12 NA

## 6 891 895 970 1 NA NA

We will use birth_weight as a response variable.

And the pedigree looks like this:

head(pedigreedata)

## id mother father

## 1 1306 NA NA

## 2 1304 NA NA

## 3 1298 NA NA

## 4 1293 NA NA

## 5 1290 NA NA

## 6 1288 NA NA

tail(pedigreedata)

## id mother father

## 1304 127 917 NA

## 1305 117 550 NA

## 1306 95 29 NA

## 1307 158 689 NA

## 1308 131 1223 NA

## 1309 144 1222 NA

Here is the simplest implementation of an animal model in MCMCglmm.

First, we load the package:

library(MCMCglmm)

Second, while not strictly necessary we think it is a good practice to convert the pedigree to an inverse-relatedness matrix. If the pedigree is properly formatted this is easily done with MCMCglmm::inverseA. The other option is to pass the pedigree directly in the pedigree argument of the function MCMCglmm, but that solution is less flexible.

inverseAmatrix <- inverseA(pedigree = pedigreedata)$Ainv

Now we can fit the model of birth_weight to estimate three parameters:

id column)model1.1 <- MCMCglmm(birth_weight ~ 1, #Response and Fixed effect formula

random = ~id, # Random effect formula

ginverse = list(id = inverseAmatrix), # correlations among random effect levels (here breeding values)

data = phenotypicdata)# data set

Note the use of the argument ginverse to link the elements of the relatedness matrix to the individual identity in the phenotypic data.

Let’s look at the results.

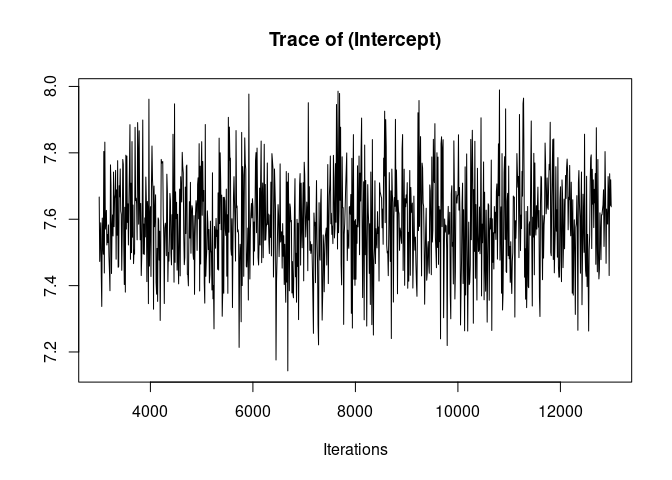

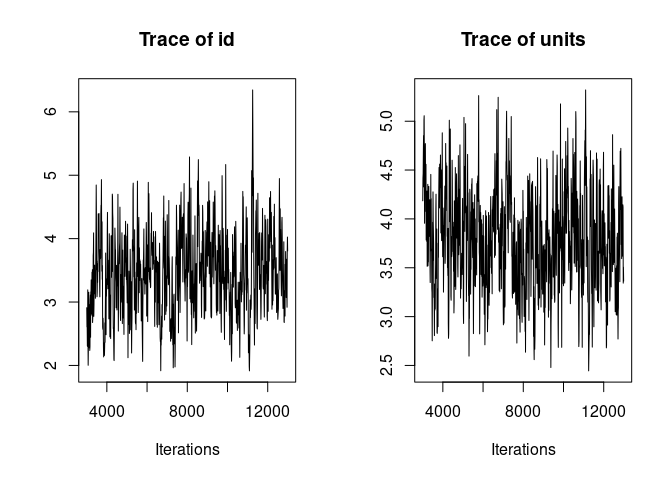

It is always a good idea to look at the trace of the MCMC sampling. Ideally we want to see “hairy caterpillars” for each parameter, that is, a stationary distribution without long-term or short-term trends across iterations. This lack of trend would indicate that the model may have converged and may have explored properly the multivariate parameter space, thus giving us reliable parameter estimates.

plot(model1.1, density=FALSE)

Here the traces of the random effect variance id and of the residual variance are not bad but show an initial trend as well as some fluctuations. We are going to re-run the model for longer to avoid those problems before we look at the results.

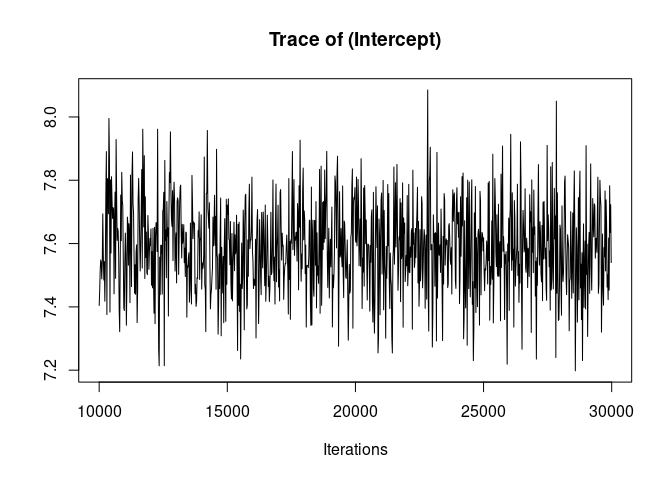

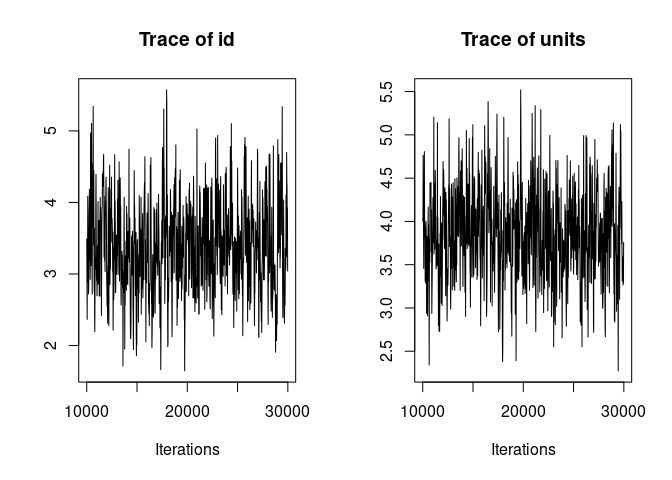

We do that by increasing the burnin value from 3000 to 10000 (this is the number of samples we discard at the beginning of the chain to remove the influence of random starting parameter values), the nitt value from 13000 to 30000 (this is the total number of samples), and the thin value from 10 to 20 (this is the interval between samples that are saved in the model output; thinning is used to reduce the memory used by the model, much of which would be made of redundant if all samples were saved because of auto-correlation in MCMC.)

model1.2 <- MCMCglmm(birth_weight ~ 1, #Response and Fixed effect formula

random = ~id, # Random effect formula

ginverse = list(id = inverseAmatrix), # correlations among random effect levels (here breeding values)

data = phenotypicdata, # data set

burnin = 10000, nitt = 30000, thin = 20) # run the model for longer compare to the default

plot(model1.2, density=FALSE)

Much better. Now we can look at the model summary.

summary(model1.2)

##

## Iterations = 10001:29981

## Thinning interval = 20

## Sample size = 1000

##

## DIC: 3913.556

##

## G-structure: ~id

##

## post.mean l-95% CI u-95% CI eff.samp

## id 3.381 2.248 4.699 381.5

##

## R-structure: ~units

##

## post.mean l-95% CI u-95% CI eff.samp

## units 3.851 2.79 4.847 419.9

##

## Location effects: birth_weight ~ 1

##

## post.mean l-95% CI u-95% CI eff.samp pMCMC

## (Intercept) 7.588 7.292 7.845 885.4 <0.001 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Among other things, the summary gives the posterior mean and 95% credible intervals for the intercept, the residual variance and the additive genetic variance.

The posterior mean is often not a great point estimate for variance parameters, because of the skew in their posterior distribution. We can obtain the posterior mode or posterior median of the additive genetic variance as

posterior.mode(model1.2$VCV[, "id"])

## var1

## 3.252129

median(model1.2$VCV[, "id"])

## [1] 3.379763

We can get the 95% credible interval of the additive genetic variance as

HPDinterval(model1.2$VCV[, "id"])

## lower upper

## var1 2.247847 4.699142

## attr(,"Probability")

## [1] 0.95

Bayesian models need what we call priors. A prior is the probability distribution of parameter values before looking at the data. So far we have not worried about it and used the implicit default MCMCglmm prior, but the default prior can cause problems. It is a good habit to specify the prior explicitly and check the results are stable under different priors.

Priors are specified as lists and can contain up to four elements in MCMCglmm:

Most of the time we will not specify B and S, which means that we keep the implicit defaults.

Each prior element is itself a list, or nested list, of parameter values. We will explain more what they mean later, but for now, here is a common prior for the model structure we have fitted above:

prior1.2 <- list(

G = list(G1 = list(V = 1, nu = 0.002)),

R = list(V = 1, nu = 0.002)

)

The prior is then added as an argument:

model1.2.p <- MCMCglmm(birth_weight ~ 1,

random = ~id,

ginverse = list(id = inverseAmatrix),

data = phenotypicdata,

prior = prior1.2, # here is the prior

burnin = 10000, nitt = 30000, thin = 20)

Here the results are almost identical to those obtained with the default prior.

Computing heritability.

Adding fixed and random effects.

How to visualise and set different priors for fixed and random effects.

How to fit and interpret permanent environment effects.

Was this page helpful?

Glad to hear it! Please tell us how we can improve.

Sorry to hear that. Please tell us how we can improve.